at the Oakland Museum. (BART is like our subway.) The

39th Annual Fungus Fair, in fact. (I think I'm 39.)

Garden clubs go starving for membership. Independent nurseries close up and go out of business. Seed companies sell out to big corporations.

Are plants yesterday's news? Is fungus is the thing now? Read any good fungus blogs lately?

I learned how to distinguish the death cap

Amanita phalloides from similar, edible varieties. The death cap lacks small striation marks around the edge of the cap. That made it seem easy to tell them apart. Well, I don't like to eat mushrooms very much, so getting confused likely won't be a problem for me.

You can see how alike the death cap is to an edible mushroom. (Left is edible; right is poisonous)

Originally from Europe, but introduced to California 100 years ago, the death cap is now very common in the Bay Area. The local news reports at least a few poisonings every year. Mushroom foraging is a popular family activity with some Asian communities.

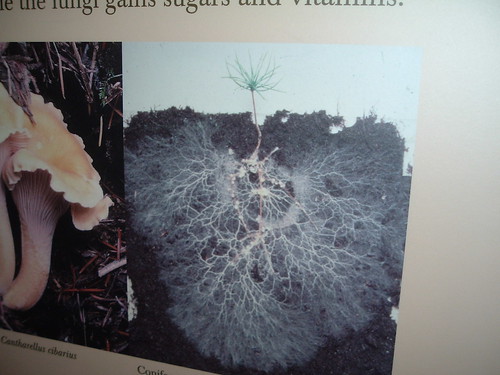

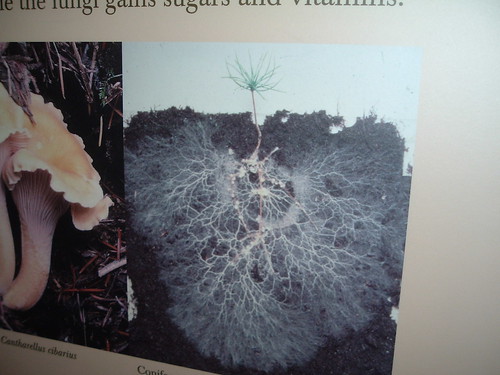

The fungus forms an ectomycorrhizal relationship with many California native plants including the Monterey Pine (

Pinus radiata) which is one of the most commonly planted plants in the world. Speaking of mycorrhyzae, here's a picture of just such a fungus-plant symbiotic relationship with a pine seedling.

You don't water California native plants during the hot summer because the water arouses dormant pathogenic fungi which quickly overtake the beneficial symbiont. The pathogenic fungi can out-compete the symbiont, and the plant dies.

I also learned that you can touch poisonous mushrooms without fear of poisoning. I thought you weren't even supposed to touch them, but I was told it's okay to touch any mushroom. (Unless, like anything else, you have a skin allergy.) You can even put a death cap in your mouth and chew--just

do not swallow.

The poison itself is a peptide (i.e., protein), like ricin from castor bean (

Ricinus communis), but unlike many plant poisons which tend to be small molecules like strychnine alkaloids or digitalis glycosides.

Mushrooms do make some small molecules however. Psilocybin, the psychoactive material in so-called hallucinogenic mushrooms is a simple chemical derivative of the ubiquitous neurotransmitter serotonin, which is known in many animals and plants, as well as mushrooms and some single-celled organisms. Walnut, pineapple, banana, and tomato all contain serotonin. (Note: anyone know about serotonin in a prokaryote?)

There were experts on hand for identifying mushrooms, and lots of tips for the amateur.

I learned where the fly agaric mushroom (

Amanita muscaria) got its common name. The mushroom has a chemical that attracts and stupefies flies. People used to put the cap in the kitchen upside down and it would fill up with flies that could be thrown out.

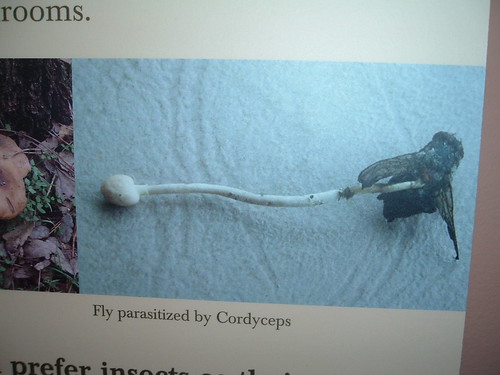

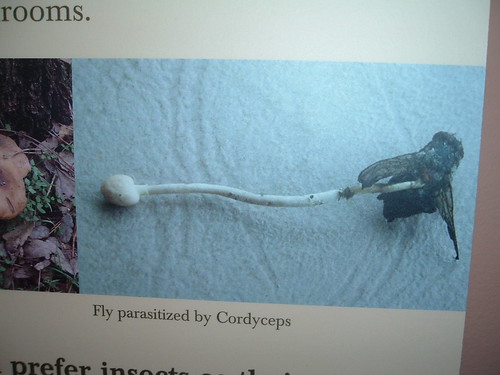

Speaking of flies, here's a picture (of a picture!) of a fly parasitized by a

Cordyceps fungi and the mushroom growing out of it. Think about the fly being converted to mushroom. Amazing. See Planet Earth Cordyceps footage

here.

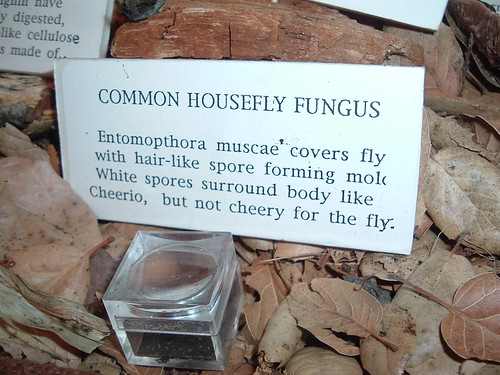

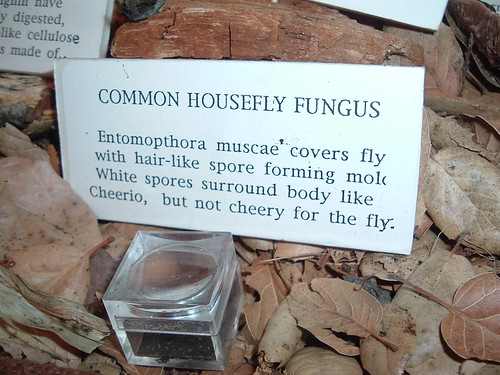

Several other fungi parasitize flies. Someone could have written a better sign for this one.

The grooviest fungus I saw today was definitely the Ballerina Earthstar,

Geastrum fornicatum. Earthstars are apparently common across North America, although I'd never heard of them until today.

When the fruiting body emerges from the ground, it starts off as a compact, round mass (you can see one at 9 o'clock in the picture above, and I don't know why there's a turtle shell in this display--please don't ask me about that). Then, when it's time to release the spores, the compact round part opens up and the "ballerina" stands up on three legs. The spores are released through an operculum on top of the round puffball that sits on top of the legs in response to a mechanical disturbance, e.g., the impact of a raindrop. If that isn't the most amazing thing you've heard today, I don't know what to tell you.

Have you heard of this before?

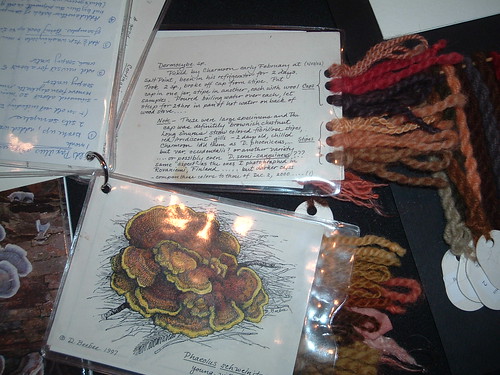

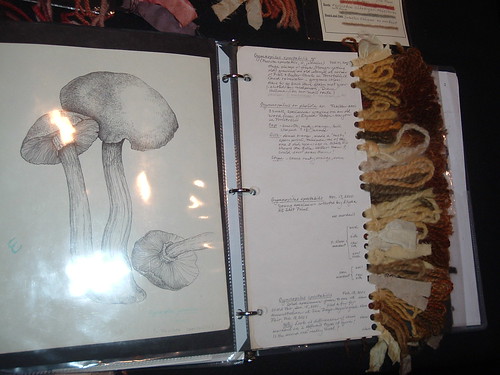

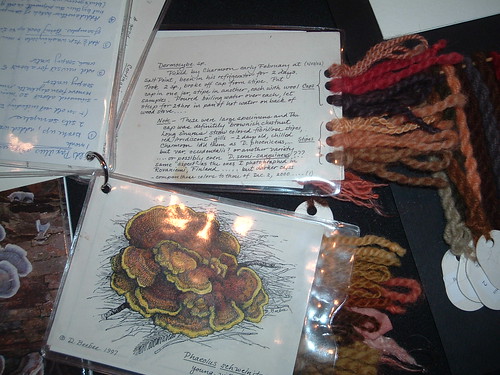

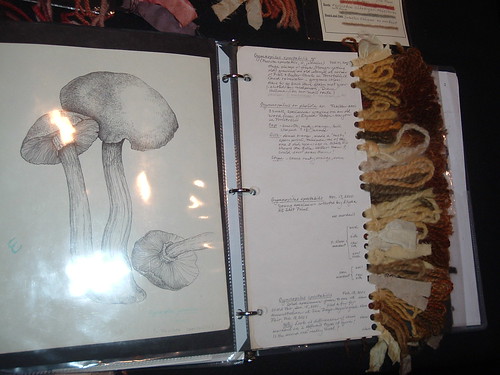

This woman brought a large collection of note cards and notebook pages about mushrooms she's collected and the different processes she used to extract pigments from them used to dye yarns. All very detailed and thorough, plus, she drew color pictures of everything she collected.

Truly, there are some remarkable people in the world.

I actually spent most of my time talking to the woman from the

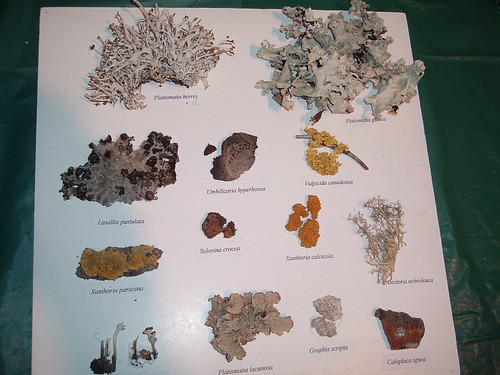

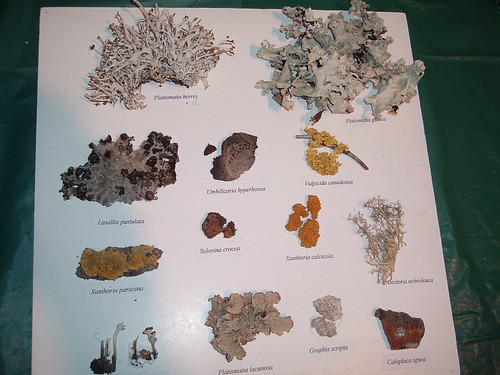

California Lichen Society. I would like to join the

California Lichen Society. California has a great diversity of lichens and apparently people come from all over the world to see our lichens. So how come I've never met a lichen tourist before?

Lichens, you may know, are fungal-algal symbiotic pairs that typically grow on rocks or dead wood or live epiphytically. Any scientific name for a lichen refers to the fungus, as the algal part is microscopic and lives inside. Apparently, a theory now is that all mushrooms have a lichen in their evolutionary past. Have you heard of the Amherst biologist

Lynn Margulis? I was reading about her

endosymbiotic theory when I got up to get a glass of milk just before the Loma Prieta Earthquake of 1989.

Margulis theorized that our cell mitochondria were originally separate organisms that were taken inside the cell as a symbiont. Now they're us. The notion of where one thing ends and another thing begins has always fascinated me. What is the manzanita without its mycorrhizae?

If none of that interests you, there was mushroom soup,

and kids doing mushroom art,

and some more awesome mushrooms.

ADDED: Six ways mushrooms can save the world,

video.